During a Congressional hearing on May 11, Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) Acting Administrator Andy Slavitt fielded questions about the recently released proposed Medicare Access and CHIP Reauthorization Act (MACRA) rule, with an emphasis on its potential impact on smaller physician practices.

Slavitt has been making the committee rounds since the release of the rule on April 27, a dramatic policy move that will be making sweeping changes to physician payment. During his testimony on Wednesday in front of the Subcommittee on Health of the Committee on Ways and Means of the U.S. House of Representatives, Slavitt said he has 35 listening sessions and calls in May alone on the MACRA rule. During the next few months, healthcare stakeholders will continue to digest the rule, with comments due back to the feds in late June.

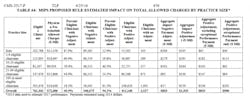

A key point of the proposed legislation brought up by multiple members of Congress at the hearing on Wednesday was a table (image below) on page 676 of the 962-page rule that outlined the details of the Merit-based Incentive Payment System (MIPS), a quality payment program within MACRA which eligible Medicare clinicians will be participating in.

In that table, CMS estimates that 87 percent of eligible solo practitioners (nearly 103,000 in total) will be hit with a negative payment adjustment in 2019, the first payment year of the program. For slightly bigger practices, the news doesn’t get a whole lot better: 70 percent of practices with two to nine physicians are estimated to get hit with negative payment adjustments, while 59 percent of practices with 10-24 clinicians will be docked, according to the estimated CMS data. In terms of dollars, these negative hits could be in the range of $100 million to $300 million, per the estimation.

Indeed, Slavitt was pressed about this table and the negative affect that MACRA would have on small practices, as predicted by the feds themselves. The CMS head said that the table is “designed to estimate the impact of these regulations on practices of various sizes. Despite what the table shows, our data shows that physicians in small and solo practices can do just as well as those in practices larger than that.”

He noted that the table looks that way because it is based on Medicare reporting data from 2014, a year in which many small and solo practitioners didn’t even report on their quality. “But in 2015, these practices’ reporting went up, and reporting will get far easier going forward,” Slavitt said. “We’re [trying to] make sure that it’s easiest on physicians to report. We are looking for additional steps and ideas as people review the rules, and our focus is on [providing] technical assistance, providing access through medical home models, and giving them the opportunity to report in groups and in a [more] automated way. We want a reporting process that is streamlined and reduces the burden for physicians,” Slavitt said.

Slavitt provided further detail on how CMS plans to help out smaller practices, noting that if they are already participating in clinical data registries, for example, that can be used for MIPS rather than requiring physicians to send information in again. Also, he said, “Small practices can report in groups in many categories where they weren’t able to before, and others won’t have to report at all if they don’t meet the minimum Medicare threshold for patients.” Answering a question from Congressman Tom Price (R-GA) about the CMS table being “damming for small practices,” Slavitt said, “I do not believe that’s the reality, but I do think we need to have dialogue about the difficulty for small practices to practice medicine.”

Since the release of the rule, the CMS Administrator said he has met with small practices in southern Arkansas, Oregon, and New Jersey, and federal officials are hearing from these types of practices often, a trend that will continue if people in Washington, D.C. make centralized decisions that impact their quality of care. “[Physicians] want the freedom to take care of patients and define measures themselves. They tell us that they know how to do it, so let them make the decisions on quality rather than have us burden them with reporting and scorekeeping,” Slavitt said.

Slavitt was additionally asked about other components of the MACRA rule, such as the 365-day reporting period that is currently required for eligible Medicare physicians. Price said there is a need to move from a full-year reporting period to a 90-day one, as “no one is perfect every day.” Slavitt noted that is one of the core areas where the government is expecting feedback.

Price also asked about frustration he is hearing from the provider community regarding aspects of the rule that are out of the hands of doctors, such as vendor data blocking and certain measures in the Advancing Care Information program. “These are things that doctors are pulling their hair out over,” Price said.

Interestingly, Slavitt was also asked about a MACRA provision that allows innovators to use qualified entity (QE) data to help doctors make smarter decisions. Bill Pascrell (D-NJ) asked, “Do you agree that the medical devices used in care, particularly for the most common Medicare procedure, joint replacements play a role in the healthcare quality and outcomes? Medicare has no information on the medical devices implanted in Medicare beneficiaries. I think we should let that settle in for two seconds. It’s extremely problematic, I think, from an oversight perspective, but most importantly from a safety perspective. So shouldn’t this information be made available?”

Slavitt’s response came off as surprising to some, saying that he believes including unique device identifiers on claims forms “has merit, particularly from a research perspective.” He committed to working with the FDA on a path forward, a stance that differs from his predecessor, Marilyn Tavenner, R.N., who in the past has resisted such a policy.

Overall, Slavitt stressed that right now, since it won’t be until the spring of 2018 when doctors will first need to report on MACRA, “The most important thing is that patients get high quality care, and if that happens, better cost control will be the result.” He added, “If someone gets the right surgery, a second one won’t be needed. Also, our job isn’t to define quality ourselves but rather to take the best standards of care that doctors and specialists have defined as quality, and keep up with that. We believe that [physicians] are the people who best know what’s right for patients. Nothing we are doing should be seen as interfering with that in any way. Rather, we need to be reinforcing those things, and MACRA does that,” he said.