In researching this book, I interviewed nearly 100 people from extraordinarily diverse backgrounds – frontline clinicians, world experts in artificial intelligence and big data, aviation engineers and pilots, federal policy makers, CEOs of major IT companies, entrepreneurs, patients and their families. Unsurprisingly, they gave vastly differing answers to many of today’s core questions in health information technology: What is the appropriate role of government? Why is usability so bad? Is Epic really open or closed? Are computers dehumanizing the practice of medicine? Will we need doctors in the future?

But when I asked folks to describe what they thought the healthcare system could look like after all the dust settles, I found a remarkable degree of unanimity. If they are right, this future state is thrilling to consider, all the more reason why the current state is so dispiriting. Moreover, given the limitations of the human imagination (who could have envisioned IBM’s Watson, or the Apple Watch, or intelligent underwear at the turn of this century?), their forecast might prove to be overly modest.

Uh oh, I can hear you thinking. I read this book because I was looking for an honest appraisal of why today’s health IT is so problematic. Has the author morphed into a hopeless techno-optimist?

But there is one thing I am sure of: the speed with which health IT achieves its full promise depends far less on the technology than on whether the key stakeholders – government officials, technology vendors and innovators, healthcare administrators, physicians and other clinicians, training leaders and patients – work together and make wise choices. So let’s take a moment to side with the optimists, painting a picture of a healthcare world transformed for the better by IT, a world that, despite our rocky start, is within our reach.

In this future state, there will be far fewer hospitals. Neither the 60-bed community hospital nor the 25-bed rural hospital will have the size and volume to produce the best outcomes. After lots of Sturm und Drang, many will prove to be economically nonviable, and will close. For the most part, this will be okay for patients (though perhaps not for the laid-off workers), since they will be able to receive most of their care in their homes or in new, less intensive community-based settings.

The hospitals that are left standing will be large, bristling with technology, and, for the most part, embedded in megasystems. Rather than the 6,000 or so hospitals that we currently have in the United States (many of them completely independent and more than half with fewer than 100 beds), the landscape will more resemble that of commercial airlines, with a handful or major national brands, accompanied by some smaller regional enterprises. Geography simply won’t matter as much in a connected healthcare world, just as it doesn’t matter to you that Amazon is based in Seattle, Fidelity in Boston, and Google in Mountain View.

Patients in hospitals will be there for major surgeries and other procedures, critical illness, or triage in the face of substantial clinical uncertainty. Anyone who is just “pretty sick” or who needs a modest procedure (including having a baby delivered) will be cared for in a less expensive setting. The concept of the intensive care unit as a discrete physical space will evaporate, as every patient who is sick enough to be in the hospital will be sick enough to need, or potentially need, ICU-level care. Each bed in the building will be wired with the technology we currently associate with the ICU, and the intensity of the care (the ratio of nurses to patients, for example) will vary on a case-by-case basis, driven by the results of sophisticated risk-modeling algorithms that will always be humming in the background. The deteriorating patient will no longer need to move to the ICU; she will simply receive the care she requires in her current location.

Patients will be in single rooms designed for safety and infection prevention. Each will be outfitted with wall-sized video screens as well as cameras capable of extreme close-ups (to allow a doctor to examine a patient’s eyes or neck veins via video) and wide angles (to see everyone in the room during a family meeting). Patients and their families will be able to review their clinicians’ notes, test results and treatment recommendations, either on the big screen or on a hospital-issued tablet computer. Patients will also receive educational materials, along with periodic messages – including encouragements (“Your goal today is to walk up and down the hallway three times”) and attaboys (“Nice work on those deep breaths today!”) – through the computer. The confused patient who begins to climb out of bed will hear the recorded voice of a trusted relative, triggered by a bed sensor: “Mom, it’s Linda. It’s okay, get back to bed.”

The nurse call button will be a thing of the past. A patient will simply say, “Nurse, I’m in pain,” and the nurse will appear on the screen, discuss the issue with the patient, and increase the pain medication if necessary. None of this will require the nurse to enter the room – a computer-entered order will adjust the IV infusion pump automatically. If a new pill is needed, it will be delivered via robot.

Physician rounds in the hospital will take place at the bedside, but they will be scheduled so that family members can participate through videoconferencing. As physicians and other team members enter the room, their names and roles will automatically appear on the patient’s screen, with their detailed bios a click away.

Consultations with specialists will be completely re-imagined. If the inpatient doctors need a nephrology consultation, for example, they will search online for a nephrologist who is available, and quickly arrange a videoconference. In the large national systems that will dominate inpatient care, the best available consultant may not be in the building; in fact, he may be in another state.The EHR will be transformed as well. The visit note will be created by physicians and other team members largely through speaking, rather than writing and clicking. Natural language processing technology will not only parse the words into the right categories in the electronic record to satisfy the demand for quality measurement and patient risk assessments, but also “tune” itself automatically as it analyzes each clinician’s manner of speech, specialty, and experience. The note’s structure will also change fundamentally: it will be a living document in which new information is added collaboratively, more like a Wikipedia page than today’s static and siloed notes created independently by each group of caregivers. Accurate historical information (family history, past medical history, and key prior studies) will be easily accessible and needn’t be reentered each time a patient receives care, partly because billing rules will no longer demand such idiocy.

Information from the record – “show me the hemoglobin trend over the past week” – will be accessed by voice command. Team members will be able to create and display graphs, images, videos, and more, for their own use and to educate patients and promote shared decision making. The technology will allow members at home to fully participate in those decisions.

Computerized decision support for clinicians will also be taken to a new level. While physicians will still be ultimately responsible for making a final diagnosis, the EHR will suggest possible diagnoses for the physician to consider, along with tests and treatments based on guidelines and literature that are a click or a voice command away. Color-coded digital dashboards will show at a glance whether all appropriate treatments have been given. Teams will develop new ways of distributing the work to be sure that all dashboards are green by the end of each shift, although many of the preventive activities (such as elevating the head of the bed for the patient at risk for aspiration) will be carried out automatically by the technology.

Big-data analytics will be constantly at work, mining the patient’s database to assess the risk for deterioration (infections, falls, bedsores, and the like) before such risks become clinically obvious. These risk assessments will seamlessly link to the dashboards, suggesting changes in monitoring, staffing, or treatments when a patient’s risk profile changes. Alerts (both those in the EHR and those from in-room monitoring devices) will be far more intelligent and far less frequent. Like the Boeing cockpit alerts, they will be graded, and the alert for “you’re about to give a 39-fold overdose” will look nothing like the alert that fires for “these two medications have a significant interaction you should be aware of.”

Physicians, nurses, pharmacists, physical therapists, dieticians, and administrators will huddle around their patients at least once a day, and the collaborative game plan they develop will be clearly captured in the EHR. But the creation of the record will, to a large degree, be an artifact of the actual delivery of care, as many of the things that doctors and nurses now type or click into the computer will be automatically entered through voice recording, by sensors (vital signs, for example), and by patients themselves. The combination of intelligent algorithms and automatic data entry will allow each healthcare professional to practice far closer to the top of her license. As less time is wasted on documenting the care, doctors and nurses will have more direct contact with patients and families, restoring much of the joy in practice that has been eroding, like a coral reef, with each new wave of nonclinical demands.

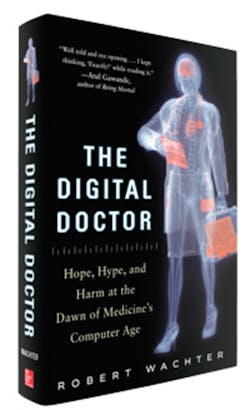

Robert Wachter, M.D., is Professor and Associate Chair of the Department of Medicine at the University of California, San Francisco. He coined the term “hospitalist” in 1996 and is generally considered the father of the hospitalist field. His sixth book, “The Digital Doctor: Hope, Hype, and Harm at the Dawn of Medicine’s Computer Age,” © (McGraw-Hill Business, April 2015, 320 pgs) is available on Amazon and through retail booksellers nationwide. This excerpt is used with the permission of McGraw-Hill Education.