A University of Michigan technology startup has spent the last decade developing a tool that extracts data from patients’ digital medical image files, such as X-rays, MRIs and CT scans, with the goal to make treatment choices far more precise for each individual.

Based in Ann Arbor, Mich., Applied Morphomics Inc. is a biomarker technology and development company that assesses body factors essential for delivering precision medicine. AMI’s analytic morphomics technology is based on discoveries from company founder Stewart Wang’s laboratory at the U-M Medical School.

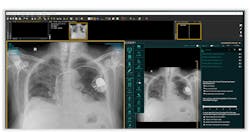

The technology extracts thousands of digital biomarkers from a patient’s medical imaging files. From this data, physicians can pinpoint a patient’s condition, the state of his or her disease and the kind of treatments that might be most helpful, according to U-M officials in a recent news release.

“This is the ultimate selfie,” said Wang, M.D., U-M professor of burn surgery. “A patient’s body is their biological medical record and contains a tremendous amount of information that clinicians to date have not been able to comprehend.”

Wang and his team began their work by analyzing millions of digital images from CT and other imaging scans of more than 100,000 patients over an almost 20-year period. From there, they were able to define baseline information about gender, age and fitness. For example, they can see that 10 years ago, children had larger muscle mass and smaller fat mass compared to five years ago as a result of lifestyle changes.

June Sullivan, managing director of the University of Michigan Morphomic Analysis Group, who was part of the team that developed the analytics tool, said the images can be shared with patients in a way medical imaging is not normally shared.

“This is a bridge between the doctor and patient,” she said. “Patients often don’t get to see their insides nor do they get a chance to talk about what their risks are. With these morphomic images, you can show them their role in their condition and treatment.”

Wang noted that the technology was developed over the past 10 years with research funding of nearly $20 million. His lab has used medical imaging scans to conduct automotive crash research to determine why some people get hurt in accidents and others don’t.

“What tends to get lost when we talk about AMI, and the inherent promise of this technology, is that there are real, concrete examples of need right now where this could be impactful,” said Drew Bennett, associate director of U-M Tech Transfer.

The technology was developed by Wang, Sullivan and other staff in Wang’s lab—assistant research scientist Sven Holcombe, former resident Hannu Huhdanpaa and program director Carla Kohoyda-Inglis. It can extract granular data on organ size and condition; muscle volume and quality from psoas and other muscle groups; visceral and subcutaneous fat volumes, distribution and density; bone mineral density; and vascular dimensions and calcification, officials said.